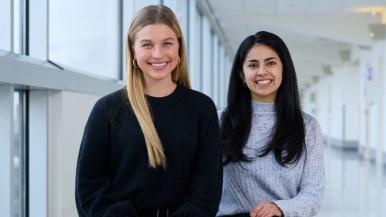

Olivia Negris and Sam Steinhall have found justice.

The second-year students at Rush Medical College were looking for more of a sense of community with their peers since the majority of classes were virtual due to the COVID-19 pandemic. That led them to the Restorative Justice Initiative at Rush University.

Negris and Steinhall soon found that restorative justice principles were changing their outlook on life and shaping the way they approach their roles as future physicians. They recently talked about the team-building concept and how it has helped them and others.

What is restorative justice?

Olivia Negris: At Rush Medical College, we use restorative justice (RJ) for community building. Traditionally, restorative justice, a practice derived from indigenous practices, is used to identify harms that have been done within a community so they can be addressed to keep individuals accountable for their actions. That promotes healing, restoration and integration back into the community.

Sam Steinhall: Formally, the definition we share with everyone is “collectively identifying the needs and harms in a given group and working collectively to repair them.” As Olivia said, though, that looks a little bit different here at Rush. We primarily work in the community-building realm rather than the harms and reparations realm.

Talk a little more about what that concept looks like within the Restorative Justice Initiative at Rush Medical College?

SS: We have team-building circles that are integrated into the curriculum. We have a curriculum that’s based on working with one another within a small group — groups of five or six people daily — so we really need to have adequate interpersonal skills.

And more importantly, we’re working to become physicians, so interpersonal skills are certainly needed in that realm. The Restorative Justice Initiative helps us work on those skills and understand how we interact with the world and the impact and repercussions of our words and actions — good or bad.

Our community-building circles include optional events where we invite students and faculty to come together and have a circle. It entails prompts or questions that everybody can speak to if they wish to. Everything is kept confidential, and we reflect upon what people say. So it can be really helpful for people who may not feel comfortable sharing those thoughts or feelings in other places.

ON: It was especially helpful last year, when Sam and I were both first-year students taking classes in a virtual setting because of the pandemic. It was something that called to us. We both wanted to get involved and promote restorative justice. The practices are very accessible, and they have helped because there was a period of time when we were missing so much of the connection that comes with attending classes live.

We’ve also had the opportunity to share RJ outside of the walls of Rush. We’ve partnered with outside initiatives through the Rush Community Service Initiatives Program, led by Dr. Sharon Gates.

Last year we worked on a program called Seeking Higher Ground, and we got to facilitate some RJ circles with students at Crane High School. We wanted to use our training to start having conversations about the utility of restorative practices with regards to things like police brutality, especially with local Black youth.

What are some other reasons restorative justice appealed to you?

ON: Medical school is a time when you work through some of your toughest moments and make some of your closest friends. Last year, there were times when the isolation from virtual coursework felt real. Though I vividly remember the first team-building circle I was a part of and appreciated how supportive and welcoming it was.

It was not something I was familiar with at all before coming to Rush. The more I learned about it and read about it, the prouder I was that Rush integrated this as part of the required curriculum.

SS: Like Olivia, last year I was really yearning for a deeper connection with my classmates. I'm also really interested in social justice and health inequities, and I feel like restorative justice has just so much power that we could harness.

What has been the most fulfilling part of your work with the Restorative Justice Initiative?

SS: When a participant comes up to one of us after a circle and says, “Wow, I really needed that space. That really allowed me to release some feelings that I felt I was harboring.” That's really powerful and makes me happy because that was how I felt when I participated in my first circle.

There’s also the community work we’re doing. It has been really cool to see how the high school students’ thought process regarding different issues has evolved utilizing the RJ circle practice.

ON: The community-building circles have been shockingly and overwhelmingly healing. It may be a light-hearted prompt that gets people to dive a little deeper and potentially turn a conversation to heavier subject matter. As board members of the group, Sam and I — along with Mary Stanley and Carter Do — are fortunate to be the ones who most often think of the prompts we want to ask and reflect on the needs of our classmates.

How do you think this experience help you as physicians in training?

ON: Restorative justice has taught me the importance of creating space to listen and reflect. I'm someone who loves to talk. I love to communicate with others. Restorative justice has taught me to be a much better listener so I can reflect and create conscious, actionable items and increase awareness within myself based on those reflections. That is going to be applicable for whatever path of medicine I decide to pursue. And just in life in general, communication and interpersonal skills are invaluable.

SS: Mindfulness is the word that comes to mind for me. Whether that's mindful listening to my patients or mindful speaking and ensuring that I'm not talking to them with medical jargon. It has helped me be aware of how my actions may affect patients and to give them the space to share their feelings. Not only that but also explicitly asking about my patients’ needs, because I think often times a patient may not be given the opportunity to fully express their needs. Allowing them to do so helps us provide the best care for them.

Why do you feel it's important for students to get involved?

SS: Both Olivia and I are second-year medical students, so our days include a lot of studying and sitting, and not too much interaction aside from class. It's easy to become overwhelmed by our studies and forget to be mindful of our actions, so I think it's a helpful practice before we start our clinical rotations.

ON: As students, we are quick to fill our days with a lot of activities we think of as resume builders or things we feel will help us be more efficient. It’s so important to take the time to care for ourselves — take the time and space to share whatever is weighing on you and be real with yourself and others.