Over the last 20 years, survival rates for advanced lung cancer have tripled. One in four cases is now caught early. The development of targeted therapies, the adoption of new screening techniques and the rise of patient advocacy groups have transformed our understanding of lung cancer and meaningfully improved the lives of people diagnosed with it. The Rush Lung Center and the multidisciplinary thoracic oncology team at RUSH MD Anderson Cancer Center are leading the way.

When Mary Jo Fidler, MD, a thoracic oncologist, began her career in the early 2000s, people diagnosed with lung cancer faced grim outcomes. The only options available to treat it were chemotherapy and radiation, and the intensity of their side effects affected the quality of life for patients with lung cancer and their families.

“So many people asked me why I wanted to work in an area of medicine with seemingly little hope for patients,” Fidler said.

Some of Fidler’s colleagues at RUSH MD Anderson Cancer Center experienced similar reactions from peers. Helen J. Ross, MD, director of research and clinical trials at RUSH MD Anderson, recalled how few clinicians were engaged in lung cancer research — and how little attention the disease received as a result.

“There was such a small number of people working in lung cancer research in the 1990s,” she said. “At conferences, it was always the last disease to be talked about, and the room was practically empty."

Lung cancer wasn’t Fidler’s original plan for her medical career. She initially set out to be a hematologist, but when her fellowship at Rush paired her with renowned lung cancer clinician-researcher Philip Bonomi, MD, those plans changed. Through his mentorship and the families she met, Fidler grew more passionate about making a difference in the lives of people diagnosed with lung cancer.

“In addition to learning and working alongside Bonomi, I engaged with innovative surgery and radiation colleagues who continually pushed the envelope to improve outcomes in lung cancer and enhance people’s quality of life,” she said.

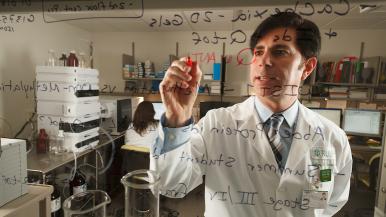

While Fidler — who was recently appointed to the Alice Pirie Wirtz Professorship of Medical Oncology — was deepening her experience in lung cancer research and care, biochemist Jeffrey Borgia, PhD, was working with thoracic surgeons and oncologists to launch the Rush Biorepository, where they could store specimens from lung cancer patients to support innovative research on a range of topics, including early lung cancer detection and blood-based tests to help guide therapy decisions.

Borgia, now director of the Rush Biorepository, didn’t plan to focus his research career on lung cancer, either. He was simply interested in how cancer works. After he delivered a presentation on proteomics, former Rush pathologist John S. Coon IV, MD, approached him about coming to Rush to develop a biomarker panel to improve early detection rates of lung cancer.

“Lung cancer had been the leading cause of cancer-related deaths, and so little was known about it,” Borgia said. “It was a discipline that was ripe for the research I was interested in: mechanistic-type studies to understand what underlies the disease.”

Driving breakthroughs at the turn of the century

Last year, the cancer field recognized the 20th anniversary of the discovery of the EGFR gene mutation as a driver in non-small cell lung cancer, or NSCLC. This groundbreaking finding catalyzed biomarker research and reshaped the field’s approach to treatment for all cancers.

“The EGFR discovery changed everything,” Fidler said. “It paved the way for targeted therapies and immune therapies that have helped patients stay alive and well five years into a diagnosis of Stage 4 lung cancer.”

Once the association was made, scientists around the world set to work designing and testing therapies that block EGFR’s signaling to cancer cells to prevent them from growing.

Rush was already participating in early trials of targeted therapy before the EGFR discovery. The close collaborations between clinicians and scientists at Rush led to ways of identifying patients who were more likely to respond to these agents and put Rush in the driver’s seat of many clinical trials that followed.

If the early 2000s ushered in the era of targeted therapies, the 2010s transformed lung cancer screening and patient outcomes.

In 2013, the National Lung Screening Trial found that low-dose CT, or LDCT, improved lung cancer survival rates by nearly 20%. It detected twice as many early-stage lung cancers as chest X-rays, which were the standard diagnostic tool at the time.

“That trial was an inflection point in the field,” Borgia said. “It helped us identify cancers sooner, before they spread.”

With a more effective tool to diagnose lung cancers earlier, the push to develop more innovative, less invasive surgical interventions gained momentum.

When Christopher Seder, MD, launched his career as a thoracic surgeon at Rush, internationally respected thoracic surgeon Michael Liptay, MD, and his team were pioneering robotic and video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for resections.

“In the early 2000s, lung biopsies and resections were open surgery operations,” explained Seder, the Arthur E. Diggs, MD, and L. Penfield Faber, MD, Professor of Surgical Sciences. “Liptay was one of the only people looking at whether resections of lung cancer through smaller incisions could benefit patients. His leading-edge research led to faster recovery, less pain and greater patient satisfaction without any changes in patient outcomes.”

Changing the outlook for people living with lung cancer

Since EGFR’s discovery, scientists have discovered more than a dozen other biomarkers associated with lung cancer, and the FDA has approved more than 100 targeted therapies to treat a wide variety of cancers, including lung cancer. In 2015, the first immunotherapy to treat lung cancer was approved. Rush served a crucial role in the clinical trials.

Meanwhile, the early detection rate of lung cancer has almost doubled in the last decade. Biopsies have become less invasive and more precise. At Rush, over 85% of early-stage lung cancer patients receive a minimally invasive lung resection.

People are living longer, more fulfilling lives because of these developments. Overall survival rates have nearly doubled, due in large part to the increase in early detection.

“It’s really exciting,” Fidler said. “The science is more advanced, and we have made great progress in individualizing care for patients with lung cancer. Patients are doing more and feeling better for longer.”

Survivors and their loved ones have harnessed this momentum to form patient advocacy groups determined to raise awareness of lung cancer and increase research funding. Rush was there in the early days as LUNGEVITY — now a multi-million-dollar organization — was getting started on the North Shore, near Chicago.

Rush researchers and clinicians celebrate the gains the field has made in part because of these groups’ tireless dedication to a future where no one gets lung cancer. Since 2000, federal funding for lung cancer research has increased 30% and awareness of lung cancer, especially in younger people and in women, has increased dramatically. These groups also expanded the availability of private funding opportunities to explore promising research questions — especially for early-career researchers.

“Patient advocacy organizations have put quality of life issues front and center,” Fidler said. “They’ve shifted the conversation from not just living longer but living well. It’s because of their efforts that we have been able to do more research into issues such as cancerrelated weight loss.”

More people diagnosed with lung cancer are also sharing their experiences to educate the public about lung cancer and the outcomes that are possible now because of research.

“I often think of my grandmother and how she passed away in 1992 from Stage 4 lung cancer,” reflected Rush patient Aurora Lucas. “My care team at Rush helped me see that my cancer isn’t going to stop me from pursuing my dreams, even though I now face a different reality in life.”

Patients such as Aurora and their stories of resilience and perseverance inspire Rush’s lung cancer experts to continue to “push the boundaries” of science and medicine.

“When you see patients in the clinic and meet their families, it’s really special,” Seder said. “I have people who say they pray for me every night because I cured them of their cancer. It’s powerful motivation for us to keep pushing the boundaries of medical knowledge.”

Improving the lives of tomorrow’s patients

Today, the Rush Biorepository contains more than 4,000 specimens and counting. As one of the largest sources of lung cancer tissues in the country, Rush contributed significantly to The Cancer Genome Atlas Program, a study conducted by the National Cancer Institute, or NCI, to map cancer genes. That study served as a beacon for molecular profiles and how they can help advance our understanding of lung cancer and accelerate the development of novel screening tools and therapeutics.

Rush oncologists, thoracic surgeons and scientists continue to collaborate on and lead large, multi-site clinical trials that are challenging and changing standards of care.

“Rush is at the forefront of new discoveries,” Seder said. “Because it’s just as important to treat the patients of tomorrow as it is to take care of patients who walk into your office today."

The medical advances made over the last 20 years have extended people’s lives significantly and reduced suffering. There are more options for personalized approaches to treatment, and more people are surviving five years after their diagnosis.

For Ross, this progress is proof we can go further.

“The first 20 years of my career, there were advances in lung cancer treatment, but the gains were small,” she said. “Today, lung cancer is no longer the disease hidden in a corner. We have momentum, and our team’s tireless commitment to a better understanding of lung cancer and developing innovative ways to address it, filling gaps in care in the hopes of giving people not just years but decades of life.”

Ross’ colleagues agree. There is still work to do to increase screening rates, predict individual patient risk of cancer recurrence, reduce the side effects of targeted therapies and personalize care plans even further, especially for people whose cancer doesn’t respond to currently available treatments.

“Each success is motivating,” Ross said. “But any time a patient’s cancer doesn’t respond to treatment as well as we’d like, my colleagues and I are motivated to find better options.”

Achieving a future where lung cancer is a more survivable, manageable disease requires long-term investments. Unfortunately, despite successful pushes for increased lung cancer research funding, it still falls short. Only 9% of the NCI’s budget goes to lung cancer research, even though lung cancer is responsible for 20% of cancer deaths.

Philanthropy helps fill the gap. It spurred the establishment of the Rush Biorepository. It has allowed Borgia and his lab to continue to build on their research and get the field closer to a more accessible tool to increase screening and early detection rates. It has given Liptay and Seder resources to lead clinical trials to improve surgical outcomes. And it has fueled experiments with 3D tumor models derived from patient tumors to develop targeted, highly personalized treatment plans for people diagnosed with lung cancer.

These and other trailblazing studies can transform how we diagnose and treat lung cancer. The Rush Lung Center’s commitment to collaboration and innovation remains key to its success.

“Rush has so much clinical power,” Borgia said. “If we can harness that potential and ensure research has the tools to explore, we’ll make a big difference in patients’ lives.”

All philanthropic gifts benefit initiatives of RUSH MD Anderson Cancer Center in the greater Chicago area and Northwest Indiana and do not fund research or programs at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.