First to perform advanced surgery for patients with medication-resistant epilepsy

Walter Whisler, MD, PhD, helped pioneer a surgical technique used worldwide to treat epilepsy when medication fails to control seizures, was instrumental in bringing one of the first CT scan machines to Chicago, and was the founding chairman of the Department of Neurosurgery at what now is Rush University Medical Center.

Whisler died Sept. 6 from complications of cancer and heart disease. He was 86.

Whisler joined Rush, at the time known as Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center, in 1970 as the first chairperson of its newly established Department of Neurosurgery (now the Department of Neurological Surgery), a position he held until 1999. Over the years, he made Rush home to one of the country’s leading neurosurgery programs. U.S. News & World Report currently ranks it as the fourth-best neurosurgery program in the United States and the No. 1 program in Illinois.

First to try a revolutionary technique

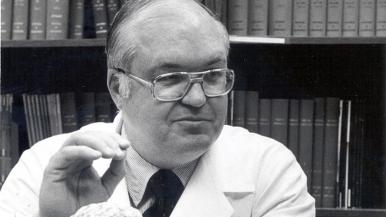

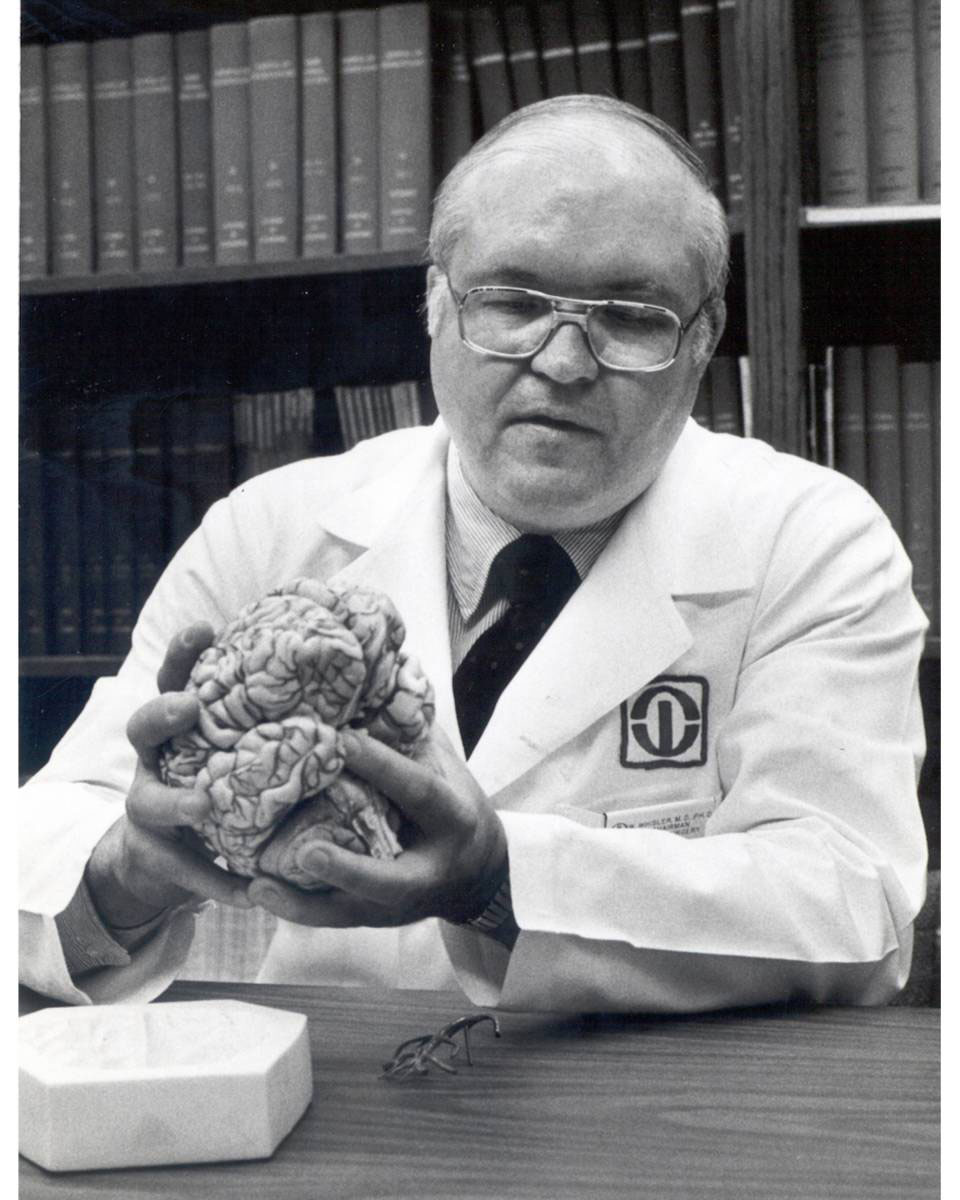

Along with the late Frank Morrell, MD, a neurologist who founded the Rush Epilepsy Center, Whisler developed a revolutionary surgical technique for medication-resistant epilepsy. Called multiple subpial transection, the treatment severs neurons in the cerebral cortex that transmit the electrical signals that cause seizures, preventing those signals from traveling to other parts of the brain, while sparing areas of the cortex used for normal functions such as speech and movement.

“Morrell had worked only with dogs, and he knew it worked but had never done it with people. No neurosurgeon would attempt it. They were all scared,” recalls Jeanette Whisler (née Engelbrecht), Whisler’s wife of more than 61 years. “But Walt believed it would work and knew he had the skill to perform the procedure.

“So eventually, Morrell and Walt carefully, cautiously did it on a patient or two, and it worked! And they did it on a few more, and they published it.”

“They would map the patient’s brain and see where the seizure traveled. Once they figured out where the wave went, they would disrupt the fibers in one direction and leave them intact in others, and that would preserve function,” says Laura Whisler, MD, the younger of Whisler’s two daughters.

A firewall against seizures

“I once heard Walt describe it as putting in firewalls to prevent the spread of seizures,” says Michael C. Smith, MD, an epilepsy specialist at Rush who trained under Morrell. “You make small incisions in the cortex, and in effect, the epilepsy can’t jump with from one area to another.”

Smith notes that about 0.3% of people worldwide have medically intractable epilepsy. “That’s a lot of people, and by getting them seizure-free, you change their lives. They can drive a car, they can get a job, they can do all these things they couldn’t do.

“He trained many surgeons from all over the world on how to do it. He wanted more people to be using this technique because he knew it would help people. Now this technique is used worldwide.”

Led effort to adopt CT scanning

Whisler pioneered another medical advance by initiating Rush’s acquisition of the first computed tomography (CT) scanner in Chicago, and the third in the United States. Now in wide use, CT scans combine multiple images from rotating X-ray machines to provide detailed cross-sectional images of the body.

“He heard through the medical grapevine that they were developing a new machine that was going to be better than X-rays. We went on a vacation to Europe and took a detour to the Karolinska Institute in Sweden to see it,” Jeanette Whisler remembers.

“He came back and talked to the radiology department about how wonderful it was and how it would be able to do all these thing we never could do before, and it would be great for neurosurgery and great for everyone. The hospital investigated it, and they bought one of the first CT scan machines in America.”

Change in direction

His humble origins did not suggest Whisler had a future in the highest echelons of medicine. He was born in Davenport, Iowa, on Feb. 9, 1934, and grew up in and near Rock Island, Illinois. Although his father, Walter Sr., a maintenance man and self-taught electrician, had only a fourth-grade education, and Whisler’s mother, Dorothy Ruth (née Carr), who worked in a department store, didn’t finish high school, Whisler and his two brothers went on to earn doctoral degrees. He still said his father was the smartest of them all.

He planned on being a machinist and working as a tool and die maker at the International Harvester factory near his home until a friend whose father was a professor, recognizing Whisler’s intelligence, suggested he go to college. “It literally had never occurred to him,” Laura Whisler says.

The first in his family to attend college, Whisler lived with his parents while attending Augustana College in Rock Island and working two jobs. His parents also helped pay for his schooling with the money they’d been saving for a new refrigerator.

Accidental romance

After graduating from Augustana in 1955, he came to Chicago, where he earned his medical degree from the University of Illinois. Throughout medical school, he worked in an epilepsy clinic and electroencephalography (brain electrical activity monitoring) laboratory of Erna and Fred Gibbs, MD — who developed the electroencephalogram, better known as the EEG — which fostered his interest in neurosurgery, particularly epilepsy surgery.

He also washed dishes in his medical fraternity in exchange for room and board there and borrowed textbooks from fellow students. “Having gone to medical school myself, I can’t even imagine figuring how to get everything done, but he had absolute, 100% determination,” Laura Whisler says.

Two days after graduating from medical school, on June 14, 1959, he married Jeanette, who had finished nursing school and her U of I degree the year before. Their meeting was literally accidental: When Whisler’s date for a formal dance was slightly injured in a car accident and unable to attend the event, one of his classmates set them up on a blind date.

She resisted at first. “He called me up and he talked me into it,” Jeanette Whisler says. “I told him all the reasons I shouldn’t go, mainly that I didn’t have an adequate evening gown, and he said ‘oh your dress can’t be that bad.’” A few sporadic dates over the course of the summer eventually blossomed into a three-year courtship.

Passion for teaching

After medical school, Whisler earned his PhD in biochemistry at U of I’s Chicago campus while Jeanette supported them working as a neuro and orthopedic operating room nurse at Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Hospital. He then completed an internship at the U of I’s Research and Educational Hospital and his neurosurgery residency at U of I, which included rotations at Presbyterian-St. Luke’s and Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital. He was appointed to the neurosurgical staff of all three hospitals in 1964.

An avid teacher, he loved delivering lectures, and one of his favorite duties at Rush was participating in resident teaching conferences. “That was his passion, to impart wisdom,” says Laura Whisler, an otolaryngologist (ear, nose and throat doctor) who received her medical degree from Rush Medical College, completed her residency at Rush and then worked as an attending physician there.

The family’s strong affiliation with Rush also includes Whisler’s younger brother Curtis Whisler, a retired Illinois Masonic orthopedic surgeon who trained at Rush; his middle brother Kenneth Whisler, a professor of biochemistry and director of laboratory information systems and services at Rush; Laura Whisler’s husband Thomas Matkov, MD, also a Rush Medical College alumnus, whom she first met in gross anatomy lab; and his other son-in-law, Jim Lochowitz, who worked in Rush’s IT department as a software developer and data architect for many years.

A widespread wealth of knowledge

“My father was a wealth of knowledge, not only about neurosurgery but how things worked,” Laura Whisler says. “Invariably, someone would be having a discussion, and he would launch into a detailed explanation about something that was relatively obscure, but germane.”

Most recently, a conversation about the COVID-19 pandemic and musical performances led Whisler to discuss the properties of unlacquered brass and its naturally occurring bacteria- and virus-killing chemical properties. “He followed it up by saying that's why in old hospitals the doorknobs are unlacquered brass. Apparently this was a common practice to prevent the spread of disease,” Laura Whisler recounts.

When she and her family returned home from the hospital after he died, her teenaged son went and sat by himself for about 15 minutes. Eventually, she went over to him, “and he looked up with tears in his eyes and said, ‘I just realized there are no more grandpa lectures.’ We will all miss those. He loved to teach.”

Whisler’s passion for sharing knowledge extended to his research publications, which included more than 60 journal articles and dozens of abstracts. Whisler also was an invited speaker at dozens of symposia and seminars nationally and internationally.

Calm in crisis

Richard Byrne, MD, one of Whisler’s last chief residents, is now the chairperson and the Roger C. Bone, MD, Presidential Professor of neurosurgery at Rush. “He was a hands-on educator, teaching by example, as is common among surgeons, because what we do is very hands-on,” Byrne says of Whisler.

“He was very good at keeping calm during a crisis, and I will always remember the things he would say to me about the extreme importance of a surgeon keeping calm during any sort of operative crisis. He was really good at that, imperturbable.”

Just how imperturbable was he? Jeanette Whisler recalls a case when a patient suffered a seizure during an epilepsy operation. Whisler and the surgical team stopped the procedure, closed the opening in the patient’s skull, returned her to her hospital room, and days later successfully completed the surgery.

“In surgery he was unflappable, never raising his voice,” says Smith, who ran the electroencephalograph during many of Whisler’s operations. “But you could tell when it got tense because he would chew his gum faster.”

A gentle giant

Laura Whisler observed a similar steadiness in her father while completing her surgery residency at Rush. “What struck me the most was his connection with his patients. He was a very caring and thoughtful man,” she says.

“He was straightforward and uncomplicated with patients. He would sit at the bedside of terribly ill patients and, without regard to time, would carefully explain and answer all their questions.

“In neurosurgery, even the good outcomes are not always good outcomes in terms of function for the patient. Diagnoses and outcomes can be utterly devastating. It takes a special personality to be a neurosurgeon, one of great understanding and empathy. He was very well suited to his profession.”

“One colleague called him a gentle giant, which was very appropriate,” Smith says. Whisler was 6 feet, 1inch tall and, according to Smith, “the size of a middle linebacker. Everything about him was big, and his hands were big, and I was always amazed how nimble his hands were.”

Principled leadership

In addition to patient care and teaching, Whisler held many leadership roles. He was president of Rush’s medical staff and a member of the Rush Board of Trustees, serving on the Board's Executive Committee. He also served on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Neurologic Drugs Committee.

In 1976, Whisler was one of the founders of the Illinois State Medical Insurance Exchange, a physician-owned company that underwrites malpractice insurance. He served as a member of the exchange's Board of Governors and Executive Committee from its inception until 2011, including two lengthy terms as vice chairman of the board.

One of his last accomplishments at Rush, and one of which he was particularly proud, was serving as chair of the Research Building Advisory Committee, coordinating between researchers and architects in the planning and space allocations for the Robert H. and Terri Cohn Research Building, which was dedicated in 1999.

Whisler also served terms as president of Illinois Neurologic Society and president, vice president and secretary of the Chicago Neurologic Society and had many appointments to committees at Rush and other medical organizations. He was a fellow in the American College of Surgeons and a member of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, the Congress of Neurological Surgeons, the American Epilepsy Society, the American Medical Association and many other organizations.

His character was evident in his leadership. “He always did what he thought was right, regardless of what was popular. While there were others who disagreed with him, they always respected him,” Laura Whisler says.

“He was one of the most honest, honorable and professional men that I’ve ever worked with,” Byrne adds.

From neurosurgery to forestry

Unsurprisingly Whisler remained very active after he retired from Rush in 1999, dedicating himself to planting and raising more than two thousand trees on a hilly former dairy farm in Wisconsin that he and Jeanette bought. “Like anything else he did, he did it thoughtfully and carefully. Before he started he studied up on forestry extensively and really planned what kinds of trees would be best to plant in various locations,” says his daughter Katharine Whisler, a supervising attorney for the city of Chicago.

He loved opera, and he and Jeanette attended nearly every production at the Lyric Opera from 1971 until last year. “He also liked country music and would listen to it while performing surgery,” Katharine Whisler says.

“He liked the country classics, and would sometimes tune into (country radio station) WUSN, but his favorites during surgeries were the Judds.” He also enjoyed the Midnight Special folk radio show on WFMT, he and Jeanette would make a point of listening to it most weekends.

He had an appetite to match his size, and loved good home cooking, but he was a fan of food in all its forms. “We would watch cooking shows together as a family. He was always wanting to try new dishes and new things,” Katharine Whisler says.

“I remember him telling the story of how when he was young, working at a grocery store, he would bring new kinds of food home to try and his mother gamely would cook it. That’s how he first tried pineapple, how he first tried pizza. There was never a new cuisine he wouldn’t try.”

“He liked nothing better than when there was some family project that involved everybody working together and having a large meal when we were done.” Those meals included Whisler’s own beef stew, which his wife and daughters proclaim delicious.

A view of the past

Diagnosed with cancer in January this year, Whisler was admitted to Rush 12 days before his passing. His room had the same view as the old neurosurgical floor where his patients had been. “He was looking out at the view he always had,” Laura Whisler says. “It really was like he was home. He’d been at Rush for so many years.”

In addition to his wife Jeanette, daughters Katharine and Laura, sons-in-law Jim and Thomas, and brother Curtis, Whisler is survived by his grandsons, Gus and Ernie Matkov, his sisters-in-law, Michele Whisler and Barbara Whisler, seven nieces and five nephews. His brother Kenneth and his parents predeceased him.

A walk-by visitation will be held on Friday, Sept. 18, from 4 to 8 p.m. at Smith-Corcoran Funeral Home, 6150 N. Cicero Avenue, Chicago. A memorial service in Whisler’s honor will be held Oct. 4 at Grace Lutheran Church in River Forest. Due to the COVID-19 virus, memorial service attendance will require prior approval, please contact memorial@phocid.net. The interment will be private.

In lieu of flowers, the family requests that donations be made to support the Neurosurgery Research Fund at Rush University Medical Center. Please send memorial gifts to Rush University Medical Center, 1201 W. Harrison St., Suite 300, Chicago, IL 60607-3319 or visit rush.convio.net/WWhisler.