History

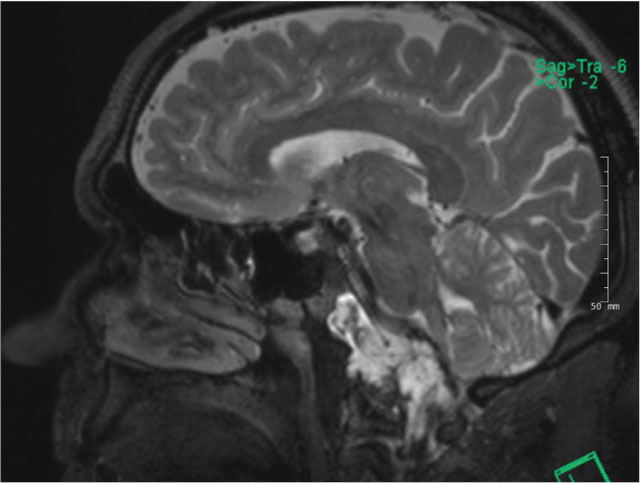

A male patient in his 60s had a history of hypertension and prostate cancer.

Presentation and examination

The patient presented with a worsening headache. His clinical exam was intact, except for some mild tongue deviation. CT imaging revealed that the patient had a clival chordoma, which measured 4.6 x 3.0 cm.

What is chordoma?

Chordoma is a rare type of low-grade, slow-growing tumor that can occur in the skull base, spine or sacrum. They are locally invasive and aggressive and are particularly challenging to treat due to their proximity to significant complex neurovascular structures, such as the spine, brain and other nerves.

Although chordomas can occur at any age, they typically affect adults between 40 and 60. About 1 in every 1 million individuals is affected by a chordoma.

Treatment

Part 1: Endoscopic endonasal approach to the clivus

This part of the procedure was performed by Dr. Papagiannopoulos.

My mission for this operation was two-fold: 1) to gain access to the tumor endoscopically; and 2) to repair the skull base defect and repair the cerebrospinal fluid leak inherent to the resection of the tumor.

In order to gain access to the tumor endoscopically through the nose, endoscopic sinus surgery had to be performed. This required endoscopically opening the bilateral maxillary sinuses, ethmoid sinuses and sphenoid sinuses. A near total septectomy was performed in order to gain access to the nasopharynx and superior clivus through a bi-nostril approach.

As the tumor extended from the level of the sphenoid down to the cervical spine, I had to perform a nasopharyngectomy, the removal of nasopharyngeal mucosa and pre-vertebral musculature, to gain access to the bone of the clivus. I then drilled down the bone of the clivus until the tumor was encountered in the extradural space.

Part 2: Endoscopic resection of the tumor, including its intradural extension

This part of the procedure was performed by Dr. Munich and Dr. Papagiannopoulos.

At this point, Dr. Munich entered the case and Dr. Papagiannopoulos assisted him in the removal of the tumor in the extradural and intradural compartments via a bi-nostril, four-handed approach. Resection of the tumor required dissecting the tumor away from vital neurovascular structures – the vertebral and basilar arteries, the lower cranial nerves (i.e. those involved in swallowing and tongue movement) and the brainstem.

After resection of the tumor, Dr. Munich and Dr. Papagiannopoulos worked together to close the large skull-base defect and high-flow CSF leak that was created inherent to the resection of this type of tumor. We harvested fat from the thigh as well as fascia lata, the lining of the quadriceps muscle, and closed the skull base defect by plugging the defect created in layers with duragen, fascia lata and fat.

Part 3: Reconstruction of the skull base and dural defect

This part of the procedure was performed by Dr. Papagiannopoulos.

I repaired the mucosal defect by using a nasoseptal flap. This is a vascularized, pedicled flap based off the posterior septal branch of the sphenopalatine artery. I harvested this flap during the approach portion of the operation, which required elevating a mucosal flap off of the left side of the septum in continuity with the mucosa from the nasal floor and lateral wall of the nasal cavity. This flap included nearly the entire length and width of the mucosa of the septum, floor of the left nasal cavity and lateral wall all while keeping the blood vessel supplying the mucosa intact. The large, pedicled mucosal flap was stored in the left maxillary sinus while the tumor resection portion of the case was undertaken.

At the conclusion of the resection and the initial layers for skull base reconstruction were placed (duragen, fascia lata, fat), I then unfurled this flap and layed it over the skull base defect. This repaired the skull base defect and helped to prevent a postoperative CSF leak. Fibrin glue and xeroform bolster were placed over the repair. The patient had a lumbar drain placed at the beginning of the operation and the lumbar drain was used to siphon 10cc of CSF per hour in the postoperative period to take pressure off of the skull base repair.

Part 4: Spinal reconstruction

This part of the procedure was performed by Dr. Fontes.

The tumor had destroyed ligaments that secured the skull to the neck area. The patient would likely have significant pain while trying to perform everyday activities and there would be risk of paralysis from the neck down if involved in a small accident.

Resecting the tumor required removing a significant portion of the bones and ligaments of the base of the skull, thus destabilizing the head and putting vital functions such as breathing, swallowing and moving extremities at risk. We performed an occipital-to-cervical fusion in order to stabilize the skull to the neck, using screws, rods and a piece of the patient’s own rib.

He had a challenging anatomy so a variety of techniques were used to place the screws for fixation. In order to allow reading, eating and going down stairs, the inserted piece of rib has to actually be aimed slightly down.

He was then placed in a hard collar for six weeks and could resume driving and most activities of daily living once the surgery healed.

Outcome

During the spinal portion of the case performed by Dr. Fontes, the patient was placed in a prone position. During the spinal portion of the procedure, there was concern for possible clear fluid dripping from the patient’s nose that could indicate possible postoperative CSF leak, despite the multi-layered closure described above.

We performed an endoscopic examination that revealed a small CSF leak in the left inferior corner of the repair. To repair this, additional fat graft and free mucosal graft were used. The patient was progressively mobilized with the lumbar drain clamped. No additional CSF leak was noted and the lumbar drain was removed. He then went to physical therapy. The patient was seen two weeks later in clinic and the packing was removed. No additional CSF leak was noted.

Overall, the patient did very well from his occipitocervical fusion and he completed his standard radiation care. He had to wear a hard cervical collar for six weeks but he is able to carry on with normal activities of his life without major problems.

Analysis

Multidisciplinary approach to complex skull base tumors

The care for patients with complex skull base tumors requires a group of highly specialized physicians and teams that include ENT (rhinologist/skull base surgeon), neurosurgery (both endoscopic intracranial/skull base neurosurgeon and spine specialist neurosurgeon) as well as medical oncology and radiation oncology.

Endoscopic access for skull base tumors

One of the biggest takeaways from a rhinologic perspective is that we can gain access to large tumors endoscopically, which can spare the patient from undergoing a craniotomy. In addition, endoscopic endonasal approaches improve surgeons’ ability to perform an en bloc resection of skull base tumors, such as chordomas, while reducing patient morbidity of existing transfacial techniques. These types of minimally invasive approaches are also garnering favorable outcomes for patients.